A woman’s drink

Something I heard at the dinner table; cocktail thoughts on hidden sexism

In Spain we have what is known as sobremesa, a term that literally translates as “the time spent at the dinner table after eating a meal”. It’s almost a ritual, specially when family or friends gather in larger groups. This post-meal period usually involves dessert, coffee, cigarettes and a drink; often alcoholic and dad humorously referred to as a “digestive”. It is also the ideal time for conversation, specially controversial topics such as politics or feminism, since etiquette dictates that one shouldn’t scream into an uncle’s face how patronizing his comment was, while still chewing a piece of steak.

Not long ago, during one of these sobremesas, a selection of alcoholic drinks were brought to the table, some so strong they resembled cologne and others that actually had a taste and were even pleasant. One of the latter was quickly labeled as “a woman’s drink”. A remark that I found kind of dismissive, considering that it was a man who had requested it and another man who coined the term. The label itself is revealing since the drink in question was simply lighter, with less alcohol, yet still very popular. Why, then, must it be gendered? I wondered.

It would be easy to let it by as a harmless banter, but it exposes the hidden (or not so hidden) sexism that coexists with us even in our most banal choices, like drink orders. Were it not so, bartenders would not so easily predict the “rightful” owner of a cocktail versus a beer. It may seem trivial, but strength continues to be coded as masculine and lightness as feminine.

This implicit hierarchy is hardly new, drinks, like clothing or social interactions have long been expected to fall into two categories. We must remember how trousers were once considered exclusively male, worn inside the cigar-filled clubs where they debated politics, art and privilege, while women were confined to their separate salons to have their own sobremesas because those topics where off limits.

Even a simple question like “Why is that a woman’s drink?” or the one that Linda Nochlin posed in 1971, “Why have there been no great women artists?” creates a sort of chain, not only refusing the assumptions of the genders, but questioning the root of them. Her answer reveals that the question itself was flawed, because women were systematically denied access to the education, institutions and opportunities that allowed that “greatness”. To expect them to achieve what they were prohibited from pursuing was absurd.

For her, then, to actually answer this question, one must shift the ground and assert that there’s a different kind of greatness for women’s art (actually, for women’s periodt) than for men’s, thereby postulating the existence of a distinctive and recognizable “feminine” style.

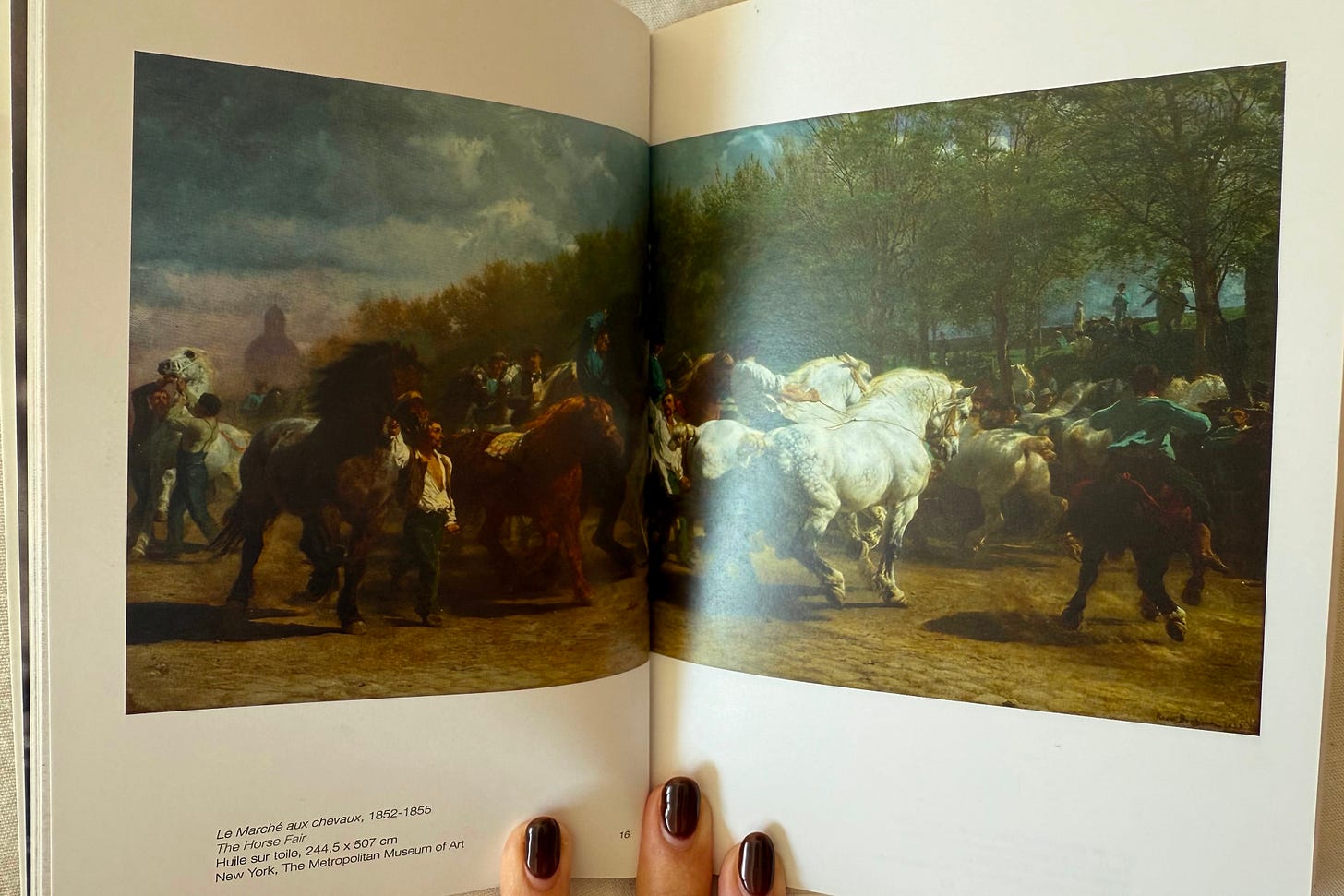

Whenever women did succeed, their work was assessed through this gendered lens, expected to carry a “feminine” quality. But then again, by those benchmarks, there is nothing “feminine” in Horse Fair by Rosa Bonheur, or at least not more than it is in The Water Lilies by Monet. By feminine if judged in terms of the binary scale of “femininity” versus “masculinity”, I wonder if Renoir paintings would have been considered by a different standard if she’d been Augusta.

The same mechanism extends beyond art. In the workplace, for instance, women often are paid less than men for equivalent positions. In everyday culture as well, women have different criteria regarding the care of a family compared to men. This perspective creates the standards in a way where it seems that the act of “lightening” or “weakening”, somehow “less”, is what institutes the feminine side. Therefore, by this, it’s not incidental for the so called “woman’s drink” to be more dainty, delicate and soft.

Paradoxically, even in fields perceived as inherently feminine, such as fashion, the great names appear to remain overwhelmingly male. As if when men step into their not so used “feminine” side, society rewards them disproportionately. Their “privilege”; that thing that they inevitably hold onto, whether they are a proclaimed feminist or not, prohibits them to acquire certain behaviors like crying or even having a cocktail.

Then, the actual medium has absolutely nothing to do with the conviction of this “greatness” but rather, just the lens with which we, as a society; that as C. Wright Mills pressed, “is ruled by norms of whats usual being seen as the natural form”, look at them and absorbe them. No wonder that “good for a woman” is still engraved in our vocabulary.

Thus, to question why an espresso martini is gendered is to begin investigating the interrogative of women’s equality, and why in art and as in any other realm, lingers on the nature of our institutional structures and the view of reality which they impose on the humans who are a part of them. The gendering of cocktails reveals that choices as trivial-seeming as a drink can both reflect and reinforce gendered power relations and acknowledging this, opens a place for everyday feminist practice.

ooh this is so interesting!! this actually gives me a lot of insight into my partner’s family - especially the time we spent together chatting after dinner. also, the amount of times that my partner has been given the lager in place of me is far too many that i can count - drinks are vessels of liquid and it’s ridiculous that they’re gendered, but that is the incredible and horrific reach of the patriarchy. great piece!

Que lástima siento por todos los que se limitan a probar algo distinto porque la sociedad en la que viven les ha dicho que no va con su género, y peor a quienes se los han prohibido.